Wellbeing

Wellbeing

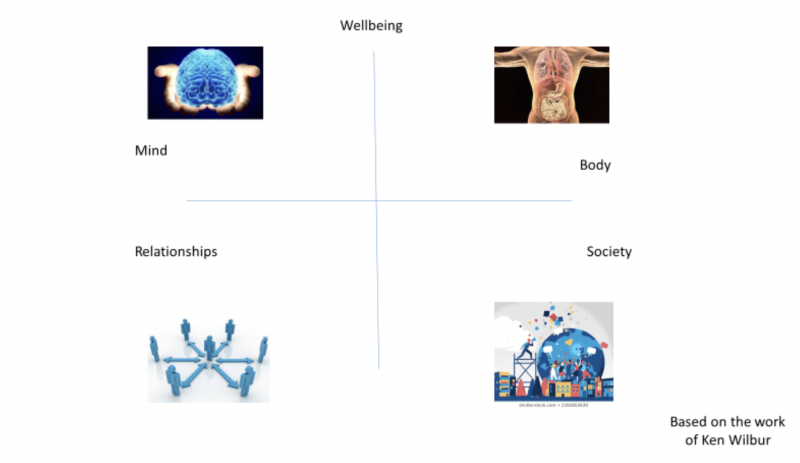

There are numerous ways in which we can conceptualise health and wellbeing. One particularly helpful model is based on the work of Ken Wilbur, and encourages us to view it from the perspective of 4 quadrants. While each quadrant has its own specific characteristics, none can operate or be seen in isolation, rather, they are interdependent.

Two of the quadrants refer to aspects of our wellbeing that are perhaps more internal. We have our own internal mental models and processes, our values and beliefs about how the world does, and perhaps should work. Our “sense of self” and the way in which we internally process our experience, has a fundamental impact on our wellbeing, contributing to our capacity for engaging with life either positively or negatively, with a resilient optimism or a fractured pessimism.

The way in which we engage with ourselves as a physical entity is another key component of our wellbeing. The extent to which we practice behaviours conducive to good health, exercising and maintaining a good diet for example, or becoming caught in cycles of more negative behaviours such as smoking, excessive alcohol consumption etc is also crucial.

Our wellbeing however, cannot be seen as the consequence of a purely individual and internal set of processes. We are a social species, and for very basic evolutionary imperatives, our wellbeing is, to a significant extent dependent upon our relationships with others. Indeed, it can be argued that it’s in our connections with others that we find our deepest sense of meaning, and that when our social connections are strong, this is when our wellbeing is at its highest. In contrast, it’s when our social connections are severed, when we feel isolated and alone, that our sense of wellbeing is at its lowest. Our need for connection, and the particular form that it takes, will of course vary from individual to individual, nevertheless, it undoubtedly plays a major contribution to our wellbeing.

Our wellbeing however, cannot be seen as the consequence of a purely individual and internal set of processes. We are a social species, and for very basic evolutionary imperatives, our wellbeing is, to a significant extent dependent upon our relationships with others. Indeed, it can be argued that it’s in our connections with others that we find our deepest sense of meaning, and that when our social connections are strong, this is when our wellbeing is at its highest. In contrast, it’s when our social connections are severed, when we feel isolated and alone, that our sense of wellbeing is at its lowest. Our need for connection, and the particular form that it takes, will of course vary from individual to individual, nevertheless, it undoubtedly plays a major contribution to our wellbeing.

While internal process and actions, along with our social relationships, are fundamental to our wellbeing, so too are wider organisational and societal factors. Our wellbeing is a both an organisational and societal responsibility, as well as an individual one.

So, for example, the extent to which I work in an environment that respects health and safety, where I feel listened to and where I believe that my contribution makes a positive difference, will all contribute to my wellbeing. More broadly, the extent to which the community and the wider society of which I am a part, provides a safe place to live, good health care and educational provision, where I have a degree of security, and where I am respected and valued, will similarly have a significant impact on my wellbeing.

So, for example, the extent to which I work in an environment that respects health and safety, where I feel listened to and where I believe that my contribution makes a positive difference, will all contribute to my wellbeing. More broadly, the extent to which the community and the wider society of which I am a part, provides a safe place to live, good health care and educational provision, where I have a degree of security, and where I am respected and valued, will similarly have a significant impact on my wellbeing.

As stated earlier, no quadrant operates in isolation. For example, if I lack self-confidence, or if I have the belief that nothing I do makes a difference, then I’m less likely to engage in healthy behaviours. If however, I have even just the one person who I know will listen to me and to whom I am prepared to speak, then I’m more likely to overcome the challenges that life puts before me.

What is clear from decades of research, and from thousands of years of human experience, is that our felt sense of wellbeing is something that we ourselves can influence. What we do, how we think, and how we organise ourselves has the capacity to change our lives for the better.